Season 3 / Episode 105

It seems likely that legislation alone won't be able to regulate the widespread use of facial recognition. Andrew Maximov, who uses AI to fight Belarus's dictatorship, shows us another way facial recognition can be used - this time for us, instead of against us.

- Episode 22

- Episode 23

- Episode 24

- Episode 25

- Episode 26

- Episode 27

- Episode 28

- Episode 29

- Episode 30

- Episode 31

- Episode 32

- Episode 33

- Episode 34

- Episode 35

- Episode 36

- Episode 37

- Episode 38

- Episode 40

- Episode 42

- Episode 43

- Episode 44

- Episode 45

- Episode 46

- Episode 47

- Episode 48

- Episode 49

- Episode 50

- Episode 51

- Episode 52

- Episode 53

- Episode 54

- Episode 55

- Episode 56

- Episode 57

- Episode 58

- Episode 59

- Episode 60

- Episode 62

- Episode 63

- Episode 64

- Episode 65

- Episode 66

- Episode 67

- Episode 68

- Episode 70

- Episode 71

- Episode 72

- Episode 73

- Episode 74

- Episode 75

- Episode 77

- Episode 78

- Episode 79

- Episode 80

- Episode 81

- Episode 82

- Episode 83

- Episode 84

- Episode 85

- Episode 86

- Episode 87

- Episode 88

- Episode 89

- Episode 90

- Episode 91

- Episode 92

- Episode 93

- Episode 94

- Episode 95

- Episode 96

- Episode 97

- Episode 98

- Episode 99

- Episode 100

- Episode 101

- Episode 102

- Episode 103

- Episode 104

- Episode 105

- Episode 106

- Episode 107

- Episode 108

- Episode 109

- Episode 110

- Episode 111

- Episode 112

- Episode 113

- Episode 114

- Episode 115

- Episode 116

- Episode 117

- Episode 118

- Episode 119

- Episode 120

- Episode 121

- Episode 122

- Episode 123

- Episode 124

- Episode 125

- Episode 126

- Episode 127

- Episode 128

- Episode 129

- Episode 130

- Episode 131

- Episode 132

- Episode 133

- Episode 134

- Episode 135

- Episode 136

- Episode 137

- Episode 138

- Episode 139

- Episode 140

- Episode 141

- Episode 142

- Episode 143

- Episode 144

- Episode 145

- Episode 146

- Episode 147

- Episode 148

- Episode 149

- Episode 150

- Episode 151

- Episode 152

- Episode 153

- Episode 154

- Episode 155

- Episode 156

- Episode 157

- Episode 158

- Episode 159

- Episode 160

- Episode 161

- Episode 162

- Episode 163

- Episode 164

- Episode 165

- Episode 166

- Episode 167

- Episode 168

- Episode 169

- Episode 170

- Episode 171

- Episode 172

- Episode 173

- Episode 174

- Episode 175

- Episode 176

- Episode 177

- Episode 178

- Episode 179

- Episode 180

- Episode 181

- Episode 182

- Episode 183

- Episode 184

- Episode 185

- Episode 186

- Episode 187

- Episode 188

- Episode 189

- Episode 190

- Episode 191

- Episode 192

- Episode 193

- Episode 194

- Episode 195

- Episode 196

- Episode 197

- Episode 198

- Episode 199

- Episode 200

- Episode 201

- Episode 202

- Episode 203

- Episode 204

- Episode 205

- Episode 206

- Episode 207

- Episode 208

- Episode 209

- Episode 210

- Episode 211

- Episode 212

- Episode 213

- Episode 214

- Episode 215

- Episode 216

- Episode 217

- Episode 218

- Episode 219

- Episode 220

- Episode 221

- Episode 222

- Episode 223

- Episode 224

- Episode 225

- Episode 226

- Episode 227

- Episode 228

- Episode 229

- Episode 230

- Episode 231

- Episode 232

- Episode 233

- Episode 234

- Episode 235

- Episode 236

- Episode 237

- Episode 238

- Episode 239

- Episode 240

- Episode 241

- Episode 242

- Episode 243

- Episode 244

- Episode 245

- Episode 246

- Episode 247

- Episode 248

- Episode 249

- Episode 250

- Episode 251

- Episode 252

- Episode 253

- Episode 254

- Episode 255

- Episode 256

- Episode 257

Hosted By

Ran Levi

Born in Israel in 1975, Ran studied Electrical Engineering at the Technion Institute of Technology, and worked as an electronics engineer and programmer for several High Tech companies in Israel.

In 2007, created the popular Israeli podcast, Making History, with over 14 million downloads as of Oct. 2019.

Author of 3 books (all in Hebrew): Perpetuum Mobile: About the history of Perpetual Motion Machines; The Little University of Science: A book about all of Science (well, the important bits, anyway) in bite-sized chunks; Battle of Minds: About the history of computer malware.

Special Guest

Ted Claypoole

Partner at Womble Bond Dickinson (US) LLP

I'm a lawyer in Atlanta, Georgia, on the FinTech Team, the Privacy and Cybersecurity Team and leading the IP Transaction Team at Womble Bond Dickinson. For more than 30 years, I have represented clients in regard to software and service agreements, data management including privacy/security/ analytics, payment systems, and technology planning. My work for current firm clients includes major financial institutions, colleges and universities, manufacturers and distributors, data security companies, software firms, hospitals and health systems, governments and government contractors.

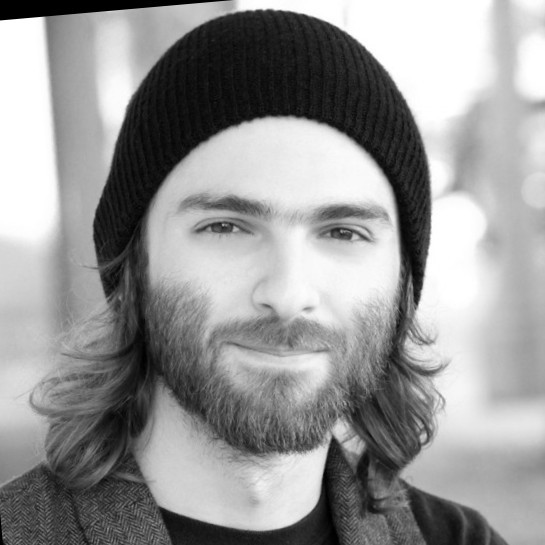

Andrew Maximov

CEO, Founder at Promethean AI

Game Industry Veteran, Technical Art Director, former Naughty Dog (Sony Interactive Entertainment), Andrew pushed cutting edge pipelines that powered some of the most complex productions in the world. Develop and Forbes magazine's 30 under 30, artist, programmer, consultant, entrepreneur and speaker at Computer Graphics events all across the globe, for years he has been fighting for democratizing the creative process, supporting artists and empowering creativity within every single person.

Facial Recognition in Law Enforcement, Pt. 2

One month before the New York Times published the story of Robert Williams, police officers killed George Floyd. We all remember the weeks that followed. The protests that broke out around the country garnered attention around the world. It was so engrossing, watching those scenes of civil strife, that an otherwise remarkable part of the story went almost entirely under the radar.

In 15 cities, the Department of Homeland Security deployed planes, helicopters and drones to watch over the protestors. The aircraft hovered over protesters in New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, feeding Customs and Border Patrol command centers, which then streamed the intel to police forces and National Guard on the ground.

In Minneapolis and D.C. a secret RC-26B reconnaissance plane worked with special ops on the ground, streaming video feeds to an FBI command center. In another instance in D.C., top Pentagon officials ordered helicopters to provide, quote, “persistent presence,” to disperse crowds. The helicopters flew so low to the ground that the sheer downward pressure from their rotor blades ripped the signs off of buildings. And, of course, it sent protestors running.

This was something out of science fiction–a full-on military intelligence operation on U.S. land.

In later reporting, military and government officials insisted that none of the aircraft deployed on protestors were equipped with facial recognition capabilities. In most cases, the aircraft were so high up that facial recognition would be moot–you can’t make out a face from a blip from 19,000 feet.

But if even some planes flew close enough to capture individual faces, it’d be problematic. According to the New York Times at least 270 hours of protest footage was captured by the aircraft, and uploaded to “Big Pipe”–a DHS network which can be accessed by other law enforcement agencies around the country for future investigations. Video in Big Pipe can be stored for up to five years. One potential concern, then, is that if a plane recorded good enough video it wouldn’t need real-time facial recognition onboard: an agency like the FBI could access that footage weeks or months later, to identify individual protestors.

It’s entirely possible that this hasn’t, and won’t happen. But around the country police have already utilized facial recognition to identify and, in some cases, arrest individual BLM protestors. The extent of it is unknown–police have no obligation to report when they run your face through a machine.

“[Ted] What concerns me is there’s currently no limits at all. None at all. So [. . .] they can also use it to take a look at everybody who is in a peaceful protest of some sort and then take down their names and hassle them or arrest them or give them trouble in one way or another or simply file them in a database as a person of interest, none of which we want to have happened to us.”

This is Ted Claypoole – a lawyer, and an author on legal issues surrounding privacy and AI. Here’s one example of what Ted means by “no limits”: it turns out you can be arrested and not even know that facial recognition played a part in it. One protestor last summer, Oriana Albornoz, was arrested for throwing rocks at a police line. That’s definitely a crime, but at no point in her processing did Miami police mention–in documentation, to her lawyer, or in any other capacity–that they used Clearview AI to identify her as the rock-thrower. It took an independent investigation by NBC News to uncover that information. And it’s important information, right? Maybe Oriana was guilty, but the next Oriana could be a Robert Williams.

“[Ted] So the issue right now isn’t necessarily the technology. It is the lack of guardrails around that technology and its use by police.”

LEGISLATION

It was amid all the BLM protests that, on June 25th, a group of Democrat lawmakers proposed the “Facial Recognition and Biometric Technology Moratorium Act.” The goal of the legislation would be, quote:

“To prohibit biometric surveillance by the Federal Government without explicit statutory authorization and to withhold certain Federal public safety grants from State and local governments that engage in biometric surveillance.”

In other words, law enforcement can only use biometric data collection with explicit legal permission, and anyone who doesn’t follow the rule will lose federal funding as a penalty.

The problem with this bill is that it won’t actually go anywhere. In fact, it probably wasn’t designed to –it’s only eight pages long, mostly comprising legal definitions of what terms like “facial recognition” and “voice recognition” mean. Seriously, there’s almost no law in this law. Most of it reads like this. Quote:

“FEDERAL OFFICIAL.—The term ‘‘Federal official’’ means any officer, employee, agent, contractor, or subcontractor of the Federal Government.”

So you get the idea–it’s a symbolic gesture more than anything. And in general, the legal effort to stop police use of facial recognition hasn’t gone much better than this.

“[Ted] Since 9/11, US society in general and legislatures in particular have been loathed to put limits around policing. They want to make sure that if someone is there to commit terrorist acts, that the police have the tools that they need to catch them.

However, during that time, I mean in other words in the last 19 years, lots of these technologies, not just facial recognition but for example other kinds of surveillance technologies like people carrying their own geo-location device in their smartphone, around with them 24/7. All of these technologies have grown up in the last 15 or 20 years and because legislatures and others have not been very interested in pinning down and putting guardrails around policing during that time, they really haven’t put any rules on it at all.”

The first, small step towards meaningful regulation of facial recognition occurred on May 14th, 2019, in San Francisco, where the city’s Board of Supervisors voted 8-to-1 to outright ban facial recognition among law enforcement agencies. Ten months later, the state of Washington signed the most expansive law in this space, requiring law enforcement to obtain legal warrants, or even provide notice and ask permission of the individual in question, before using facial recognition. Among many other provisions, it also states that agencies must regularly test the algorithms they use for accuracy and biases, then report results back up to the state.

Washington’s law could be a sign of the future but, in all likelihood, it won’t be. It is, of course, the only state of its kind with such strict rules. Even San Francisco’s case is, ultimately, very weak because it’s just city law. If you’re a protestor in San Francisco, San Francisco police can’t use facial recognition against you, but the National Guard doesn’t have to follow the same rules, or the FBI, or even California state police.

“[Ted] I think possibly if the American Bar Association put out some statements, policy statements that they believe that this is the best way to use this technology from a Fourth Amendment standpoint, to use it within the bounds of the constitution. That might help.

But really what we probably need to see is some place like the State of California take this up as an issue and then pass a law on it because really when you have a big state that takes leadership on this role, then everybody else seems to look at it carefully.”

YOU CAN’T STOP PROGRESS

Perhaps legislation will one day regulate facial recognition on a wider scale. But history demonstrates, over and over again, that you can’t stop progress. Technologies get better and become more widespread over time as a rule, so there’s little reason to think that facial recognition won’t become incredibly accurate and completely pervasive in our society years from now. The universe where governments stop using this technology out of concerns for individual privacy seems much more unlikely than the universe where it becomes so normal that we all just get used to it.

For those of you who believe that facial recognition is good because it prevents crime, that’ll be a good thing. For those of you suspicious of law enforcement, or protective of your privacy, it’ll be a creepy dystopia.

But it doesn’t have to be.

The universe you’re picturing now–where cameras are everywhere and governments are constantly tracking you with your face–is conditioned in some respects by all the science fiction we’ve seen and read over the years. In most sci-fi, biometric data collection is something that happens to us, against us. A lot of those stories don’t consider how the very same technology can be used by us.

INTRO TO ANDREW/BELARUS

“[Andrew] My name is Andrew Maximov. I’m Founder and CEO at Promethean AI and video game developer with about a decade and a half of experience.”

Andrew Maximov isn’t an activist by trade. He cut his teeth as an art director for the “Uncharted” series–some of the most popular video games in the world. But earlier this year, he turned his attention to an entirely different kind of project. To understand why, you first need to understand the political situation in his home country of Belarus.

“[Andrew] Belarus has been widely referred to as the last dictatorship of Europe. [. . .] I mean it’s an extremely unfortunate situation really. It has been that way for the last 20, 26 years.”

Ever since the dissolution of the Soviet Bloc, Belarus has been under the control of a single leader: Alexander Lukashenko.

“[Andrew] [it is an] authoritarian regime that made people disappear all the way back in the ‘90s and nothing much has changed. [. . .] People are routinely pursued, jailed, persecuted or exiled for their political opinions, whether they act on them or just sort of espouse them publicly.”

According to Reporters Without Borders, Belarus is the most dangerous country for journalists in Europe. Political opposition leaders are routinely forced to flee the country, or worse.

“[Andrew] There has been five presidential elections and none of them have been widely recognized as free or fair.”

On August 9th, 2020, Lukashenko was reelected president for the sixth time. Or, to put it more accurately: his side claimed victory. There’s little doubt that the actual vote counts didn’t matter. So, as they did the last time Lukashenko got elected, protests broke out. And, as they did the last time protests broke out, some dissidents were met with violence.

“[Andrew] I think the prevailing feeling that you have growing up in a dictatorship is the one of hopelessness and helplessness and that never goes away. You carry that with you and just as much as that, you also carry the guilt for not being able to protect people to the left and to the right of you as you see them being beaten up or arrested by the thugs in uniform who pretend they represent the law in some capacity.”

FACE COVERINGS

There are lots of videos posted to social media where Belarusian police are either violently apprehending or actively beating up civilians. In most of these videos, the police are wearing face coverings. At first it’s perfectly understandable: during COVID, everybody should be wearing masks.

But you get the sense that it has nothing to do with COVID. The police wore these masks before the pandemic and, frankly, there’s nothing medical about them. They’re usually ski masks, and they only sometimes cover the nose. In one video, a police officer’s mask covers his nose but ends above his mouth. Clearly, this isn’t about germs.

“[Andrew] They cover it routinely because – well, I’m pretty sure most of them are well aware that they’re not doing something that society as a whole would appreciate. [. . .] if it gets into the post-COVID days, I’m sure no one is going to be taking off their masks anytime soon.”

The police wear masks so they can do what they want to protestors, and not be held to account for it. It’s not an uncommon phenomenon. Throughout the George Floyd protests, for example, video captured officers taping over their badges, or wearing no identifying information on their uniforms whatsoever.

“[Andrew] Because one of the more effective ways of applying pressure to them is just the social training comparably and there’s a – people, you know, protesting with posters that say, “De-anonymization saves lives,” because in some cases is does.”

THE VIDEO

Andrew lives in L.A. now, so he couldn’t participate in the protests. But he did come up with a novel way of contributing to the cause.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FAJIrnphTFg

That’s Andrew, in a video posted to YouTube on September 24th, 2020. Translated, he says: “your children will be looking at your faces when you commit the most despicable acts of your life.”

The video has over one million views–pretty good for a country of less than ten million people. It was an instant success because of just how radical the concept was. In the video, Andrew demonstrates diligently, case by case, a software he built that de-masks violent police.

It’s pretty wild. For five minutes he takes clips of police violence, freezes them, and demonstrates how his algorithm can interpret only the facial features that are shown–eyes and a nose, sometimes just the eyes alone–and map it onto an actual person’s face.

“[Andrew] For all those that will continue to terrorize, everybody in their life will know what you did. The driver you will lock eyes with when crossing the street with your family, groups of laborers or young guys that you will be passing by at night, the doctor who will be treating your kids, they will all know what you did. You are supposed to defend the people of Belarus.”

HOW IT WORKS

“[Nate] Tell me about the technology in this video and how it works.

“[Andrew] It was actually quite surprising how – surprising and disturbing how easy it was to put together a facial recognition tool. You can conceivably do it in an afternoon. That is the scary part. Like, you know, a high schooler with a laptop could do that.

[. . .] They’re a bunch of off-the-shelf computer vision models or facial recognition models that you can leverage and [. . .] They just have this deep neural layer that somehow represents some facial features which is like a multidimensional representation spread around, whatever, 50 neurons, right? That would define all kinds of things that [. . .] come out as to representing an individual face in a particular image for example.

Then all we have to do, right, is just scrape a whole bunch of images, build a library of those faces and then compare them to other faces. So in this case in Belarus, there’s just a general effort for de-anonymization, right? There are just people posting pictures of policemen. There are Telegram channels because that has proven harder for the government to shut down [. . .]

You can write – there are APIs for literally anything. You can build an Instagram bot that people can submit this to. You can, yeah, have a client that will just scrape it automatically. You can do it by hand. In my case, I actually just tapped a few other people to help literally save every relevant image that they find because the sort of communal solidarity is quite strong [. . .]. that helps build up that library of people without the masks. They actually just run that model, extract the features and then you just run the same thing over the people with the masks and all the other photos. You know, freeze frame from the videos that they have incoming and then you get a certain amount of matches with a certain amount of confidence and you know, you can sort of manually check on top of that.”

Once he has a match of high confidence, Andrew superimposes the maskless picture over the masked one, and does a little bit of digital reconstructing along the way.

“[Andrew] The actual facial reconstruction is a little trickier. It’s also a little harder to do off the shelves. [. . .] But it is also quite doable.”

It’s not a perfect system–sometimes the superimposed faces look a bit cartoonish. But they also, for the most part, seem pretty accurate.

“[Andrew] Any type of AI tools, none of them are ever 100 percent correct, just period, because they all work based off the data set that they’ve been trained on and they’ve been obviously known to have biases to be complete.”

To supplement the algorithm, Andrew used his and his colleagues’ own eyes to try and verify their results.

“[Andrew] There should always be a human to validate and verify.”

MISIDENTIFICATION

Andrew’s video is a proof of concept: that facial recognition can be used not just by police against civilians, but civilians against police. That opens up a whole, big can of worms.

“[Nate] One of the things that occurred to me when I was watching your video is it goes back to the question of accuracy. We’ve – you know, obviously you wouldn’t have created and published what you did if you didn’t think the results were accurate. But is it the consequence of even getting one of these wrong just extremely high? Like you could end up accusing the wrong person of very bad things and have them go through what you intend the people you get, right, to go through.

[Andrew] I don’t think any program can be effective enough that you don’t worry about it. That’s a huge concern and yeah, and we did get one person wrong. So that was not a joke for me absolutely and that’s a responsibility that you have to own up to. Once again there were no people that were not associated with the Armed Forces and the person that we got wrong was an ex-policeman that was fired from the Force because he was extorting bribes from businessmen. [. . .]

They were very upset with us understandably and to me, I think it’s just a matter of the greater good, right? I mean I – you have to take on that responsibility which I wouldn’t wish for anyone in the world to have to do because if it has any chance of tempering the violence even in the slightest, then it might be worth it because the discomfort of an ex-policeman compared to literally thousands of people that are jailed and beaten up on the street, it just doesn’t weigh up.

I know that in an ideal world, you want to make sure that nobody ever gets hurt as a consequence of what we do and I perfectly understand that. But yeah, it’s just the question of having to make a call and at that time, it was up to me to make one and well, yeah, I have to live with the consequences of that, yeah.”

SHARING THE ALGORITHM

Misidentifying one of the police officers, for an audience of one million people, is something that Andrew has to live with now. But it’s not his only burden.

“[Andrew] I’ve been getting tons of requests from people to just like release this and this obviously sounds like a recipe for disaster to me.”

A lot of Belarusians–and non-Belarusians–understandably wanted their hands on this software. Andrew decided not to distribute it.

“[Andrew] it was a terrible decision to have to make because – even to this day, I get emails from people all over the world who are in a similar situation saying, you know, they’re getting brutalized, they’re getting beaten and they feel like their government is failing them and they don’t have any way to protect themselves really because the government has the monopoly in violence and there are no checks and balances in a lot of places. Unfortunately a lot of the time US included as well.

That is just heartbreaking. But, you know, I literally – I put the project on hold the moment I was working on the part that could just arbitrarily scrape any website for matches because that had just seemed like a – the whole thing just for me…I would rather this did not have to exist at all. That’s the sad part of it. Like the ethical concerns are ridiculous.

And while there’s no future where the police are not going to be as easily identified as everybody else who they identify, I definitely do not want to be the police in a sense, meaning abusing those tools and [. . .] especially with the opportunity for misuse because someone could have as easily used this tool. I don’t know, stalking their ex-girlfriend or their ex-wife or something much more sinister and that is terrible.

So just having that as a public tool is terrifying to me.”

CONCLUSION

The question of this episode has been: should law enforcement use facial recognition? We discussed how effective it’s becoming at catching criminals, but also how biased it can be, and how prone it is to misuse.

It turns out that was the wrong question. What we should really be asking is: how can we deal with facial recognition, and all the power it gives to whoever uses it? This is a technology that can cause extreme harm, whether by facilitating an Orwellian dystopia where Big Brother is always watching, or by identifying–or misidentifying–somebody who could be greatly harmed for being exposed for whatever they’re on camera doing, good or bad.

The question is will we, as a society, be like Andrew? Will we recognize the power in this technology, and the power of its misuse, and address it in time to avoid terrible consequences?

Probably not. Law enforcement won’t regulate itself, and this is still too fringe an issue for most Americans to care about, so politicians are generally better off not touching it.

“[Ted] At the moment putting limits on police force makes it look like you oppose law and order. So whether that’s right or wrong, that has always been an attack from one side against the other is all of your – if you’re saying the police can’t do this, that means you’re on the side of the criminals. You know, and legislators are very, very sensitive with those attacks.”

More likely than not, law enforcement agencies will continue to collect your biometric data, even if you don’t want them to. And at some point, somebody will build a software like Andrew’s and release it for public use.

Because there’s no stopping technological progress. You can only ride the wave, and hope not to crash.

Latest episodes

Latest episodes

Subscribe

Subscribe